The Standards of Practice set out the minimum standards in paramedic services. Each regulated member is required to understand and comply with these Standards, but how does this translate in the day-to-day work of EMRs, PCPs and ACPs?

In an effort to help regulated members understand and apply the Standards to real life situations, the College has put together a variety of scenarios that give context to the Standards and ideas on how to implement this into practice.

As you may already know, the Standards of Practice set out the minimum standards in the provision of paramedic services. Each regulated member is required to understand and comply with these Standard but how does this translate in the day-to-day work of EMRs, PCPs, and ACPs?

In an effort to help regulated members understand and apply the Standards to real life situations, we will be launching a series of scenarios that give context to the Standard and ideas on how to implement this into practice.

The following scenarios will attempt to address Conflict of Interest:

Example A – Patient Care:

Paramedics Mel and Sandy are working a shift together in Airdrie, a suburb of Calgary. They are nearing the end of a busy shift when they get a call an hour before their shift ends. The patient has suffered a possible stroke, and the transport protocol for stroke patients is to transfer the patient to the Foothills hospital, which is near the centre of Calgary, and it is rush hour traffic.

Both Mel and Sandy have family commitments after work, and they know taking this patient to the Foothills hospital will definitely result in overtime, and they would be unable to meet their familial obligations. They decide to downplay the patients’ symptoms and transport to the Airdrie Urgent Care Centre.

Without going into the potential violation of employer policies and the College’s Code of Ethics, we can see that there is a conflict of interest between the paramedics’ desire to meet their familial commitments and their obligation to the patient’s specific needs.

Example B – Employment Responsibilities:

Joe works for EMS Ambulance which has a contract to provide medical coverage at an arena for sporting events and concerts. After working a few of these events, Joe strikes up a relationship with the Director of Operations at the arena and they begin to talk about the current contract with EMS Ambulance. Joe divulges that EMS Ambulance has had numerous issues related to staff turnover, keeping equipment in working order and maintaining the appropriate level of supplies. Joe also divulges that the owner of EMS Ambulance often brags about how lucrative the arena contract is.

Over the course of a few months, Joe convinces the Director to go to market for the contract to provide medical coverage for the arena events. Meanwhile, Joe has formed a company and places a lower bid to provide the same services as EMS Ambulance. Ultimately Joe’s company wins the bid.

While this example doesn’t relate to patient care, it does present an alternative situation where a conflict may exist or be perceived. Joe’s role as an employee of EMS Ambulance is to professionally represent EMS Ambulance while covering these events, but conversations with the Director undermined the credibility of EMS Ambulance. Joe’s decision to form a company to place a competing bid creates a clear conflict of interest where Joe’s financial interest is positioned against the duty to professionally represent their employer.

As you may already know, the Standards of Practice set out the minimum standards in the provision of paramedic services. Each regulated member is required to understand and comply with these Standards, but how does this translate in the day-to-day work of EMRs, PCPs, and ACPs?

In an effort to help regulated members understand and apply the Standards to real life situations, we will be sharing scenarios that give context to the Standards and ideas on how to implement this into practice.

The following scenarios will attempt to address Duty to Report and unprofessional conduct issues:

Scenario A:

Tiffany and Joe have been partners for two months and Joe is always late for work. This has resulted in the off-going crew incurring additional overtime and is creating a rift in the working relationship between the two EMS crews. Tiffany is fed up with Joe’s behavior and has tried talking to him about this, but he was dismissive and continues to arrive late for his shift.

Tiffany should follow employer protocol to address Joe’s behavior and poor performance. Although Joe is being disrespectful to his coworkers, his behavior does not constitute unprofessional conduct.

Scenario B:

Joe and Tiffany are doing a non-urgent patient transport from Banff to Calgary. Tiffany is in the back with the patient and Joe is driving. During the trip, Tiffany notices that Joe is constantly hitting the roadside rumble strips and when they pull into the hospital ambulance bay, Joe strikes the curb while attempting to park. After they transfer care, Tiffany finds a half empty bottle of alcohol hanging out of Joe’s duty bag. Tiffany confronts Joe and he admits to having “a few sips to calm his nerves” during the transfer.

Tiffany should immediately report this to her employer and the College. Joe’s behavior puts both the patient and his partner at risk and Tiffany has a duty to report as she certainly has reasonable grounds to believe that Joe’s actions would be considered unprofessional conduct.

The Standards of Practice are essential to ensure quality care is provided to all Albertans by all healthcare professions. These Standards not only provide direction to regulated members in the provision of care but also explain elements of care that patients and the public can expect in their professional interactions with regulated members.

The College’s Standards of Practice (or SoPs) were recently completely rewritten and released in July 2021. These Standards expanded on many areas that the former version did not include – and they now provide a lot more detail on the expectations of care that is to be delivered by regulated members. While it is expected that as a regulated member you familiarize yourself with the content, the College is also here to help provide clarity on areas as questions arise.

The Standards of Practice, Self-reporting (1.4) can be an area of uncertainty or confusion for members and much of this uncertainty comes from misconceptions or misunderstandings.

1.4 Self-reporting

A regulated member must immediately self report to the Registrar the following:

- Any relevant details including any physical, cognitive, psychological and/or emotional condition that may negatively impact the regulated member’s work or is reasonably likely to negatively impact their work in the future.

- A sexual relationship with a patient.

- New or updated criminal charges brought against them.

What exactly does this mean for regulated members?

SoP 1.4.1 speaks to the physical and psychological conditions that may impact a member’s ability to provide care. This part of the SoP does allow for the member to self-evaluate the condition and make their own determination about self-reporting based on how or if the condition will impact the care they provide.

SoP 1.4.2 does not allow for the same level of self-evaluation. Sexual relationships with patients are a serious matter, and under Bill 21, the government has required all regulatory colleges to develop a separate Standard on this topic, complete with predetermined sanctions. The Standards of Practice, 2.0 Patient Relationship can be referenced for more information.

SoP 1.4.3 also does not allow for self-evaluation, as new or updated charges against a member must be reported as per the Health Professions Act (Sec 127.1(4)) which states:

A regulated member must report in writing to the registrar, as soon as reasonably possible, if the regulated member has been charged with an offence under the Criminal Code (Canada) or has been convicted of an offence under the Criminal Code (Canada).

Reporting a charge to the College does not necessarily mean that the College will take any punitive action. It is only in very extreme circumstances where the College may need to take some form of sanction against the member if the charge is deemed to present a reasonable and potential risk to the public.

Self-reporting unprofessional conduct

Regulated members have a duty to inform the College if they have been found guilty of unprofessional conduct by another regulatory college or governing body. As per the Health Professions Act:

- 127.1(1) If a person is a regulated member of more than one college and one college makes a decision of unprofessional conduct with respect to that regulated member, the regulated member must, as soon as reasonably possible, report that decision and provide a copy of that decision, if any, to the registrar of any other college the person is a regulated member of.

- (2) If a governing body of a similar profession in another jurisdiction has made a decision that the conduct of a regulated member in that other jurisdiction constitutes unprofessional conduct, the regulated member must, as soon as reasonably possible, report that decision and provide a copy of that decision, if any, to the registrar.

- (3) A regulated member must report any finding of professional negligence made against the regulated member to the registrar in writing, as soon as reasonably possible, after the finding is made.

Self-reporting to the College may seem like a daunting task, however, it is a requirement for all regulated members under the HPA and our Standards of Practice. Many members may fear that self-reporting might result in the end of their career in paramedicine, it simply isn’t the case. While there are instances where punitive actions must be taken against members, that is not the intention of self-reporting and the College is committed to working with members through these circumstances.

Members looking to self-report any breaches in conduct can do so on the website through the following form: Self Reporting Form for Members – Alberta College of Paramedics (abparamedics.com)

If you have any questions or concerns, please contact the College at Conduct@ABparamedics.com.

As you may already know, the Standards of Practice set out the minimum standards in the provision of paramedic services. Each regulated member is required to understand and comply with these Standards, but how does this translate in the day-to-day work of EMRs, PCPs, and ACPS?

In an effort to help regulated members understand and apply the Standards to real life situations, we will be sharing scenarios that give context to the Standards and ideas on how to implement this into practice.

The following scenario will attempt to address protected titles:

Scenario:

Max is a PCP working in Edmonton and one day while looking online for a landscape company, he came across a website called the Plant Paramedics. Since he is a PCP, he knows that ‘paramedic’ is a protected title and this company provides landscaping and planting services. Max is not sure what to do.

The College takes the use of protected titles seriously and has developed a Standard of Practice related to this topic. The titles we are authorized to use while providing health services are not only granted to us so that registrants are clear on the health services that each of us can provide, but also to serve as an indicator to the public about the level of care they can expect from each designation. The College’s authority in ensuring that protected titles are used properly are extensive and significant fines can be imposed if a title is misused while providing care to the public.

Upon initial review, one might think that this company and its employees are misusing the title of “Paramedic”, and that the College should step in and put a stop to it. Although this scenario is fake, the College has had similar situations occur. We did seek a legal opinion of the use of the “Paramedic” title in this type of situation and we were informed by a regulatory law firm that…

No person shall use the title… “paramedic”… alone or in combination with other words in connection with providing a health service unless the person is authorized to use the title or abbreviation by this Act or another enactment.

The key point they made was that the use of the protected title alone does not constitute misuse unless it is done so where it was accompanied by an expectation of providing a health service. The ‘Plant Paramedics’ are clearly offering landscaping and planting services, and as such, the College would not pursue any claims of misuse of a protected title. This type of title use occurs frequently with the title of “Doctor”, such as “Windshield Surgeons Auto Glass” or “the Rug Doctors Carpet Cleaning”. Neither of these businesses convey that they would be offering health services and therefore there is no misuse of a professional title.

Conversely, consider this situation at a pipeline construction site. The OH&S Code requires this particular site to be staffed by advanced first aiders (AFA’s), and one of the AFA’s consistently identifies themselves to the site manager as “the onsite Paramedic”. While this may seem innocuous at first glance, there can be significant repercussions. If the site manager believes that the AFA is an actual paramedic and appreciate the higher level of care that paramedics can provide, certain emergent situations may be directed to the AFA who would not be able to manage to the same degree as a registered PCP or ACP, such as cardiac chest pain or severe shortness of breath. This could delay response times and result in a negative patient outcome, and situations like these should be addressed.

If a registrant of the College is aware of anyone that continually and intentionally misrepresents themselves by misusing any of the protected titles, they should attempt to inform this individual and make them aware that misuse of protected titles has serious repercussions. If it continues, it would be appropriate to report this to the College so that we can follow up on these matters.

As you may know, the Standards of Practice set out the minimum standards in paramedic services. Each regulated member is required to understand and comply with these Standards, but how does this translate in the day-to-day work of EMRs, PCPs, and ACPS?

In an effort to help regulated members understand and apply the Standards to real life situations, we will be sharing scenarios that give context to the Standards and ideas on how to implement this into practice.

The following scenario will attempt to address communication:

Scenario:

Jimmy is a new EMR to the profession and just starting his professional career in his early twenties. He is very passionate about his job and loves helping people. In his free time, he makes TikTok videos with his friends and has developed a following online. Recently, he has started sharing information about his work as an EMR, posting stories from his job while in uniform and providing his opinions on specific treatments that his coworkers provided to certain patients.

In one of his most popular posts, he referenced an event in a small town where their ambulance was dispatched to assist another crew with an obese patient with back pain. He openly critiqued his colleagues for administering pain medications (Morphine as per protocol) and lifting the patient onto the stretcher then into the ambulance and went on to state that patients in this situation should “just take Tylenol and drive themselves to the Emergency Department.”

Regulated members are fully within their right to have social media accounts, identify as a medical professional online or publicly, share information about medical practice and speak to personal experiences online or in public. However, members who identify online or in public as healthcare professionals are still bound to their responsibilities as a member of a regulated health profession. These include practicing (including providing education) within your scope of practice, maintaining privacy and consent and adhering to the Standards of Practice and Code of Ethics.

In the scenario above, Jimmy’s comments regarding the administration of opioid pain medication are beyond his scope of practice as an EMR. Further, his comments advising other patients in similar situations to take specific drugs and drive to the ED could be viewed as providing medical advice that again would be outside his scope of practice as an EMR. The College’s conduct department would be required to investigate this behavior and may likely result in remediation.

It is important to understand your responsibilities communicating with the public regardless of if you are on the job or not, especially if you are identifying yourself as a healthcare professional. It is also important to recognize that social media is pervasive, almost always permanent and out of personal control once posted. We encourage members to keep the Standards of Practice, Code of Ethics and other regulatory responsibilities in mind when posting online or communicating in public as an identified healthcare provider.

As you may know, the Standards of Practice set out the minimum standards in paramedic services. Each regulated member is required to understand and comply with these Standards, but how does this translate in the day-to-day work of EMRs, PCPs, and ACPS?

In an effort to help regulated members understand and apply the Standards to real life situations, we will be sharing scenarios that give context to the Standards and ideas on how to implement this into practice.

The following scenario will attempt to address collaboration.

Understanding the Standards: Collaboration

As you may know, the Standards of Practice set out the minimum standards in paramedic services. Each regulated member is required to understand and comply with these Standards, but how does this translate in the day-to-day work of EMRs, PCPs, and ACPS?

In an effort to help regulated members understand and apply the Standards to real life situations, we will be sharing scenarios that give context to the Standards and ideas on how to implement this into practice.

The following scenario will attempt to address collaboration.

Scenario:

Kevin is a licensed EMR working for a fire department that offers medical first response outside of Calgary. He is an active member of the fire department and remains on-call for any medical emergencies in his surrounding community. Kevin is woken from sleep one night for a motor vehicle collision that occurs outside of his community. Kevin heads to the scene of the incident in the fire response vehicle. Kevin is the first medical responder on scene and is advised that an ambulance crew is dispatched as well. Kevin begins to provide patient care to an adult male and female patient who self-extricated from the truck, which appears to have drove into the ditch and rolled.

As Kevin is providing care, 2 more fire department members and the ambulance arrive on scene to assist. The ambulance crew heads to Kevin for a patient update and to assess the need for transport for both patients. During assessment and treatment of the patients, Kevin realizes that some of the needs of the patients are outside his scope of practice, such as the initiation of an IV and analgesia for pain control. This prompts Kevin to proceed to give a hand over report to the incoming ambulance crew, which consists of a PCP (Jordan) and ACP (Shauna).

When delivering the hand over report to the EMS crew, Kevin communicates and shares his knowledge for the benefit of both the male and female patient. After the hand over report occurs, the EMS crew invites Kevin to continue to assist in providing care for both the male and female patient as they both need transport to the hospital. Kevin is willing and able to continue monitoring vital signs for both patients as Shauna (ACP) initiates treatment and Jordan (PCP) initiates transport to the closest medical facility. Once the EMS crew and Kevin arrive at the hospital with the patients, a formal handover report is delivered by Shauna to the hospital staff. She also checks in with Kevin and the patients to ensure that there are no misunderstandings during handover, actively demonstrating collaboration while facilitating an integrated approach to patient care.

In this example, Kevin, as well as the EMS crew, demonstrates their knowledge and adherence to the Standards of Practice, Collaboration (1.7), in which a regulated member works collaboratively to facilitate an integrated approach in the provision of quality care. Kevin demonstrates this by consulting with others and providing a smooth transfer of care when the patient’s needs fall outside the regulated member’s scope of practice/training/competency. Both Kevin and the EMS crew also demonstrate it by communicating appropriately and sharing knowledge and expertise with others for the benefit of the patients. Finally, Kevin, Jordan, and Shauna demonstrate collaboration by engaging relevant healthcare providers and the patients to prevent misunderstandings, manage differences and take positive action to mitigate/resolve any conflicts.

As you may know, the Standards of Practice set out the minimum standards in paramedic services. Each regulated member is required to understand and comply with these Standards, but how does this translate in the day-to-day work of EMRs, PCPs, and ACPS?

In an effort to help regulated members understand and apply the Standards to real life situations, we will be sharing scenarios that give context to the Standards and ideas on how to implement this into practice.

The following scenario will attempt to address conscientious objection:

Scenario:

Don is an Advanced Care Paramedic, working in a northern community. Don and his partner, Sarah, are tasked by dispatch with picking up a patient from their local community care home and transporting this patient back to a home residence in the country. When Don and Sarah arrive at the care center they proceed to the front desk for a handover report from the nurse in charge. They find out the reason that the patient is being transferred home today is because the patient will be ending their life through the Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) program. The nurse also requests that while enroute to the residence if an IV could be initiated for pain control due to the gravel road and the rough ride ahead.

After Don and Sarah receive the handover report, Sarah approaches Don to discuss with him her objections to being a part of this transfer, on the grounds that it conflicts with her conscience and religious beliefs. She also contacts her Supervisor to consult and advise on the situation as well.

The supervisor is aware of the Standard of Practice 1.8 – Conscientious Objection and lets Sarah know that she does not have to be involved in the transfer and will send another member to complete the transfer with Don. As the nature of this transfer is not time sensitive, Dispatch, the hospital and the patient are advised that a different paramedic will come swap out with Sarah and that it will take approximately 30 minutes for the next unit to arrive and pick up the patient.

Prior to sending another member – the Supervisor discusses the sensitive nature of the transfer with the alternate paramedic, Lindsay, and ensures both Don and her are comfortable with completing the transfer. Both paramedics agree that they are willing to participate in transferring the patient back to their home residence to comply with their directives in the MAID program. They are also comfortable with starting an IV and initiating the pain control protocol for the duration of the patient transfer home.

In this example, Sarah and her Supervisor demonstrate their knowledge and adherence to the Standard 1.8 – Conscientious Objection in which a regulated member may conscientiously object to providing medically necessary care on the grounds that it conflicts with the regulated member’s Charter freedom of conscience and religion.

As you may know, the Standards of Practice set out the minimum standards in paramedic services. Each regulated member is required to understand and comply with these Standards, but how does this translate in the day-to-day work of EMRs, PCPs, and ACPS?

In an effort to help regulated members understand and apply the Standards to real life situations, we will be sharing scenarios that give context to the Standards and ideas on how to implement this into practice.

The following scenario will attempt to address human health research:

Scenario:

Olivia is the Training Officer for an integrated fire service. Her department is presented with an opportunity to participate in a research study aimed at improving pre-hospital care for burn patients. Before agreeing to participate, Olivia thoroughly reviews the study protocol, ensuring that it aligns with ethical principles and is approved by an appropriate research ethics board.

Once satisfied with the ethical considerations, Olivia ensures that all members of her department understand that they need to obtain informed consent from patients or their legally authorized representatives before including them in the study. This involves providing clear explanations of the study’s purpose, procedures, risks and potential benefits in a manner that is easily understood by participants.

Throughout the study, Olivia ensures that the members of her department diligently follow the established research protocols, accurately documenting patient data and interventions according to specified guidelines. They maintain confidentiality and privacy at all times, ensuring that patient information is securely handled and anonymized for analysis.

As the study progresses, all members of the department remain vigilant for any adverse events or unforeseen complications, promptly reporting them to the research team and taking appropriate action to ensure patient safety.

Upon completion of the study, Olivia contributes to the dissemination of findings through presentations, publications, or other means, adhering to principles of academic integrity and transparency.

In this example, Olivia demonstrates adherence to Standard of Practice 1.9 by actively engaging in human health research with a commitment to ethical conduct, patient safety and the advancement of pre-hospital care practices.

As you may know, the Standards of Practice set out the minimum standards in paramedic services. Each regulated member is required to understand and comply with these Standards, but how does this translate in the day-to-day work of EMRs, PCPs and ACPS?

In an effort to help regulated members understand and apply the Standards to real life situations, we will be sharing scenarios that give context to the Standards and ideas on how to implement this into practice.

The following scenario will attempt to address defining prohibited medical procedures.

Scenario:

Bev is an experienced Advanced Care Paramedic (ACP) working in the urban center of Calgary, a city known for its diversity and large immigrant community. Bev has always taken pride in maintaining the highest standards of care and professionalism, and she’s well-respected in the community for her ethical conduct, clinical skills and commitment to patient well-being.

One day, Bev and her partner are called to respond to a home residence. The call comes through as a 20-year-old female patient (named Amina) in acute pain, potentially from a complication following a medical procedure. Upon arriving at the scene, Bev and her partner find Amina in significant pain and distress. Bev’s first priority is to assess the patient’s immediate medical needs. After completing a thorough physical exam, she discovers a healing wound that is highly concerning: it appears to be a recent incision or excision around Amina’s genital area, showing signs of infection and significant swelling. The wound is consistent with a procedure known as female genital mutilation (FGM), a practice that is both illegal and medically dangerous. Amina is now experiencing complications, including severe pain, infection and difficulty urinating, which prompted her to seek medical attention.

Amina is reluctant to speak about the procedure, but with patience and reassurance, she shares a few details with Bev explaining she underwent the procedure a few weeks ago following pressure from someone in her life. The procedure was performed by a family acquaintance who had recently completed medical school. Amina was told the procedure was necessary for her health and well-being and his training in school had prepared him to initiate this surgery.

Bev immediately recognizes the gravity of the situation. Not only is the practice of FGM illegal in many countries, including Canada, but it is also a form of gender-based violence with severe physical and psychological consequences for the patient. As an ACP, Bev is bound by professional ethical standards, and her responsibility is clear: she must ensure Amina receives proper medical care and report this incident to the relevant authorities.

Bev and her partner administer pain relief and initiate appropriate medical treatment for the infection and any immediate threats to Amina’s health. Bev then informs Amina of her options, ensuring she understands that she has the right to seek further legal and medical support. Bev also knows that the next step is a crucial one. According to Standard 1.3 – Duty to Report, she is required by law and ethical standards to report any healthcare provider who has performed or procured an illegal medical procedure, including FGM, if she believes, on reasonable grounds, that it has taken place. This is not just a moral obligation—it’s a legal one.

Bev then initiates immediate action. She contacts the appropriate regulatory body and law enforcement to report the incident. The report is made in strict confidence, and Bev’s primary concern is Amina’s safety and well-being, as well as ensuring that the physician involved is held accountable for their actions. She is careful to document the situation thoroughly, noting Amina’s statement and the medical findings, which she shares with the authorities to support their investigation. While Bev is deeply disturbed by the violation of Amina’s rights and the harm she has suffered, she remains focused on her duty to protect her and others from further harm.

In this example, Bev demonstrates her knowledge and adherence to the Standard 1.8 – Prohibited Medical Procedures, in which paramedic professionals are expected to conduct themselves professionally and ethically while providing the highest quality of care. It is the responsibility of all regulated members to ensure they are performing up to date, legal and ethical medical procedures. A regulated member must not perform or procure illegal medical procedures including, but not limited to, female genital mutilation. In the above case, the acquaintance that performed the illegal procedure of FGM on Amina was in breach of this Standard.

Additionally, the Standard goes on to say that a regulated member has a duty to report as outlined in Standard 1.3 if they believe, on reasonable grounds, that another healthcare provider has performed or procured or is performing or procuring illegal medical procedures including, but not limited to, female genital mutilation. Bev and her partner did a good job of identifying an illegal medical procedure and took the appropriate steps to report their findings while also providing exceptional patient care.

As you may know, the Standards of Practice set out the minimum standards in paramedic services. Each regulated member is required to understand and comply with these Standards, but how does this translate in the day-to-day work of EMRs, PCPs, and ACPS?

In an effort to help regulated members understand and apply the Standards to real life situations, we will be sharing scenarios that give context to the Standards and ideas on how to implement this into practice.

The following scenario will attempt to address privacy and confidentiality:

Scenario:

Matt and Amy are paramedics in Edmonton. They are called to a house and on arrival they find a group of young adult females. The ladies are insisting their friend is experiencing abdominal pain, but she (the patient) is downplaying her symptoms and appears to be uncooperative with needing medical help. Matt and Amy start to try and get a history from their patient, but she is not providing full answers and is avoiding questions. At this point, Matt decides to gather all the bystanders and bring them into a separate room. This allows Amy to try to work with their patient in private and Matt to get a detailed account of the events from the friends.

While there may be many reasons patients refuse to be cooperative with paramedics, Matt bringing all the other bystanders into another room gives the patient the opportunity to provide private or confidential medical information they may not be comfortable providing in public.

It is important to remember privacy is often a key component for members of the public to feel comfortable with medical providers.

As you may know, the Standards of Practice set out the minimum standards in paramedic services. Each regulated member is required to understand and comply with these Standards, but how does this translate in the day-to-day work of EMRs, PCPs and ACPS?

In an effort to help regulated members understand and apply the Standards to real life situations, we will be sharing scenarios that give context to the Standards and ideas on how to implement this into practice.

The following scenario will attempt to address consent. This will be a two-part series as we will be explaining the difference between informed consent and implied consent.

Scenario:

Don is a seasoned PCP working near the remote community of Rainbow Lake. Don is dispatched to an industrial site for a 52-year-old male complaining of “chest tightness”. Upon arrival at the industrial site, Don and his partner Lindsey are greeted by the Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) Officer on site who guides them to the medical trailer where the patient is located. The OHS Officer lets Don and Lindsey know that this gentleman has already stated he did not want to be taken to hospital or go through the process of flying out of camp, but he is open to getting an assessment done. Don and Lindsey thank the Officer for this information and proceed to enter the medical trailer to perform their assessment on the 52-year-old male.

Don and Lindsey enter the trailer and observe a 52-year-old male patient, Henry, sitting in a tripod position, looking diaphoretic and quite anxious. They proceed to introduce themselves as paramedics and let Henry know the nature of their proposed examinations while inviting him to ask any questions that he might have. Henry, while seeming skeptical and reiterating that he wants to stay at work, agrees to let them assess him before any treatment or transport decisions are made. Don immediately takes the lead and begins to obtain a chief complaint and medical history on this call while Lindsey obtains a full set of vitals.

After Don and Lindsey have completed their assessment, they inform Henry of their assessment/diagnosis and proposed treatment. Because Henry is showing signs and symptoms of cardiac-related chest pain, they tell him they would like to perform a 12-lead, initiate an IV and administer some medications. Henry at first is reluctant and states he believes it to be some indigestion and asks for some Tums. Don and Lindsey let Henry know that he has the right to give or withdraw consent prior to them performing any treatments or administering medications. They also ensure that Henry understands his condition could be very serious and come with many potential risks, including cardiac arrest. They go on to explain further what a 12-lead and IV initiation is and what medications would be appropriate.

After hearing Don and Lindsey fully explain the treatment plan and the risks and benefits that accompany that plan, Henry provides verbal consent to allow for a 12-lead to be performed, an IV initiated and medication administration. Don and Lindsey proceed with the treatment plan and let Henry know that they will keep him informed of their findings and will discuss what transport decision might be best, respecting Henry’s right to withdraw consent at any time.

In this example, Don and Lindsey both demonstrate their knowledge and adherence to the Standard 2.2.1 Informed Consent, where regulated members must communicate to and discuss with the patient the indications, risk of harm and contraindications of treatment (including medication) to enable the patient/alternate decision maker to be able to provide informed consent prior to treatment. Both paramedics were able to provide information to their patient about the assessment, diagnosis and proposed treatment, as well as give him the opportunity to ask any questions. They informed Henry of the benefits and risks of the proposed treatment as well as the risks associated with not getting any treatment and remaining at camp. They received informed consent from their patient and respected that Henry had the right to withdraw that consent at any time.

As you may know, the Standards of Practice set out the minimum standards in paramedic services. Each regulated member is required to understand and comply with these Standards, but how does this translate in the day-to-day work of EMRs, PCPs and ACPS?

In an effort to help regulated members understand and apply the Standards to real life situations, we will be sharing scenarios that give context to the Standards and ideas on how to implement this into practice.

The following scenario will attempt to address consent. This is part two of a series explaining the difference between informed consent and implied consent. Part one can be found here.

Scenario:

Don is a seasoned PCP working near the remote community of Rainbow Lake. Don is dispatched to an industrial site for a 52-year-old male complaining of “chest tightness”. Upon arrival at the industrial site, Don and his partner Lindsey are met by the Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) Officer on site who guides them to the medical trailer where the patient is located. The OHS Officer lets Don and Lindsey know that this gentleman, named Henry, has previously stated he did not want to be taken to hospital or go through the process of flying out of camp, but he was open to getting an assessment done. Don and Lindsey thank the Officer for this information and proceed to enter the medical trailer to perform their assessment on the 52-year-old male.

As Don and Lindsey enter the trailer, they observe a 52-year-old male patient actively collapsing to floor while grasping his chest. They attempt to introduce themselves as paramedics and let Henry know they are there to help. The patient is not able to track Don and Lindsey, nor is he able to converse with them as he is unconscious with agonal respirations. Upon further assessment, Henry remains unconscious, unresponsive and unable to provide informed consent in regard to his own medical assessments and treatments. At this point, Don and Lindsey determine that implied consent exists, despite the patient not being the one who called for emergency medical services. Additionally, because Henry is involved in a life-threatening health event (such as a cardiac event) that renders him unable to provide informed consent, it is assumed that implied consent is given to Don and Lindsey to initiative CPR and life-saving measures in this circumstance.

In this example, Don and Lindsey both demonstrate their knowledge and adherence to the Standard 2.2.2 Implied Consent, where a regulated member who attends a patient who is unconscious, unresponsive or otherwise unable to provide informed consent may reasonably determine implied consent exists if the patient was the one who called for emergency medical services but was unconscious, unresponsive or unable to provide informed consent upon the regulated member’s arrival. Additionally, in this scenario, the patient was also involved in a life-threatening health event (such as a cardiac event) that rendered him unable to provide informed consent.

As you may know, the Standards of Practice set out the minimum standards in paramedic services. Each regulated member is required to understand and comply with these Standards, but how does this translate in the day-to-day work of EMRs, PCPs and ACPs?

In an effort to help regulated members understand and apply the Standards to real life situations, we will be sharing scenarios that give context to the Standards and ideas on how to implement this into practice.

The following scenario will attempt to address disclosure of harm.

Scenario:

Jenny is a casual ACP working on an ambulance in suburban-rural setting, just outside of Edmonton. Jenny is working with her PCP partner, Kathleen, who recently completed her mentorship. Early in their shift, Jenny and Kathleen are called to a 42-year-old male experiencing an anaphylactic reaction in the community of Alberta Beach. Upon arrival, Jenny and Kathleen are ushered into a home residence by the patient’s wife who seems to be very distressed, explaining that her husband must have eaten something with peanuts. They walk into the kitchen and find a 42-year-old man in the tripod position, experiencing severe shortness of breath as well as swelling and hives to his face and neck. Jenny and Kathleen begin patient assessment and initiate care.

During the course of immediate intervention, Jenny instructs Kathleen to draw up a dose of epinephrine and administer that as soon as possible while she (Jenny) is initiating the IV and setting up the cardiac monitor. Unbeknownst to Jenny, Kathleen is feeling very overwhelmed and flustered in this moment. Kathleen has never provided care to a patient experiencing such severe anaphylactic symptoms, and she begins to experience cognitive overload. While Kathleen is familiar with the dosage of epinephrine that she is to give, Kathleen mistakenly administers the epinephrine intravenously, rather than intramuscular. Before Jenny realizes what Kathleen is doing, she witnesses Kathleen unscrewing the syringe from the IV line.

Jenny immediately attempts to confirm the six rights of medication administration with Kathleen, who quickly realizes the mistake she just made. Both practitioners verbalize to one another that there has been a medication error and quickly reassess their patient to monitor for any changes. While he is still in distress and experiencing tachycardia post medication administration, it seems that his condition is starting to trend in the right direction. Kathleen and Jenny continue to monitor for life-altering symptomology due to the medication error.

While Jenny and Kathleen prepare the patient for transport, Kathleen (in collaboration with Jenny) advises both the patient and his wife of what just occurred – ultimately disclosing to them the harmful medication error. Jenny, being the ACP and senior practitioner, goes on to disclose that the harm was a result of an error and was preventable, as well as the steps they (as practitioners) must do to follow up this adverse event. Both the patient and his wife are unhappy with the medication error but understand and appreciate the disclosure of the harm he experienced. Both paramedics will also be following up this incident with appropriate reporting to the hospital, employer, and ensure appropriate documentation in the care report.

In this example, Jenny and Kathleen both demonstrate their knowledge and adherence to the Standard 2.2 Disclosure of Harm, where a regulated member must appropriately disclose harm. Disclosure of harm addresses the patient’s immediate and future medical needs, the investigation (if required) of the circumstances that led to the patient suffering harm, and necessary steps to prevent recurrence of the harm if an untoward and avoidable event occurred.

As you may know, the Standards of Practice set out the minimum standards in paramedic services. Each regulated member is required to understand and comply with these Standards, but how does this translate in the day-to-day work of EMRs, PCPs, and ACPS?

In an effort to help regulated members understand and apply the Standards to real life situations, we will be sharing scenarios that give context to the Standards and ideas on how to implement this into practice.

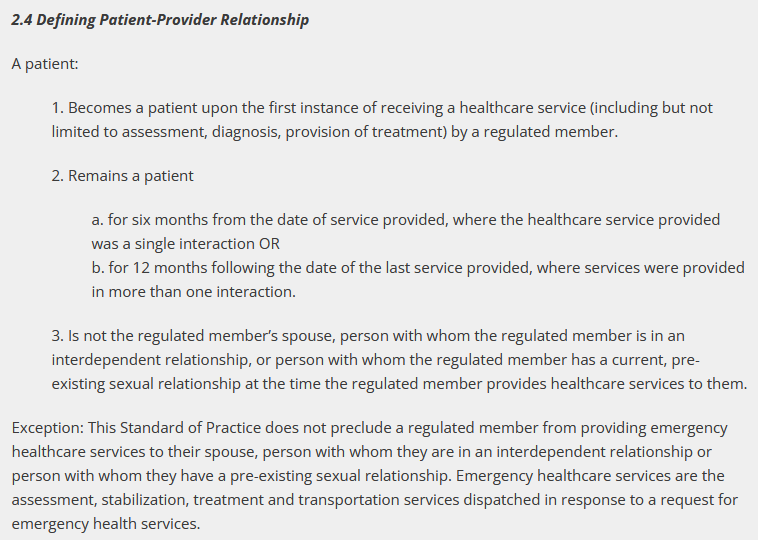

The following scenario will attempt to address defining patient-provider relationship.

Scenario:

Olivia is a Primary Care Paramedic who works and lives in her rural community of High Prairie. Olivia frequently gets called to emergencies at residential homes of people that she is acquainted with due to her connections within the community. While she is off shift, she runs into a young man, Jeff, that she used to go to high school with. He is interested in taking her out for a coffee to catch up. Olivia realizes that she responded to a motor vehicle collision (MVC) that Jeff was involved in five months ago. Olivia decides to look into the Standards set out by the College to find out what constitutes a patient-provider relationship before agreeing to coffee with Jeff.

Note: Olivia is not in an interdependent relationship or a pre-existing sexual relationship with Jeff. Additionally, Jeff is not Olivia’s spouse.

Olivia consults the standards when she arrives home. She realizes that Jeff is considered a “patient” and she is considered a “provider” under the standard. He is considered a patient because she assessed his injuries and provided treatment by splinting his wrist at the scene of the MVC five months ago. She understands that Jeff will remain a “patient” of hers for six months from the date of the MVC accident.

Olivia also considers if she has assessed, diagnosed and/or treated Jeff on more than one instance – which she has not- as that would constitute Jeff being a “patient” for 12 months from the last date of service being provided.

She lets Jeff know that he is still considered her “patient” and advises him of the timeframes and criteria set out by the Standard. Olivia decides to wait to have coffee with Jeff until there is no longer a patient-provider relationship.

In this example, Olivia demonstrates her knowledge and adherence to the Standards of Practice, Defining Patient-Provider Relationship (2.4), in which a patient becomes a patient upon first instance of receiving a healthcare service by a regulated member. This patient remains a patient for six months from the date of service provided, where the healthcare service provided was a single interaction or for 12 months following the date of the last service provided, where services were provided in more than one interaction. She also recognizes that a patient is not the regulated member’s spouse, person with whom the regulated member is in an interdependent relationship, or person with whom the regulated member has a current, pre- existing sexual relationship at the time the regulated member provides healthcare services to them.

As you may know, the Standards of Practice set out the minimum standards in paramedic services. Each regulated member is required to understand and comply with these Standards, but how does this translate in the day-to-day work of EMRs, PCPs, and ACPS?

In an effort to help regulated members understand and apply the Standards to real life situations, we will be sharing scenarios that give context to the Standards and ideas on how to implement this into practice.

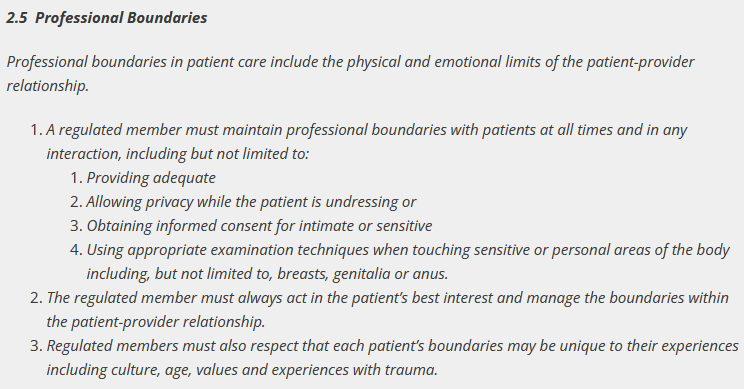

The following scenario will attempt to address Professional Boundaries:

Scenario:

Todd is an Advanced Care Paramedic working for an industrial oil company. He works as the stand-alone medical provider onsite and must be available for any medical emergencies that may arise. While on shift, Todd is called to attend to a 52-year-old female who is complaining of shortness of breath and chest pain. He arrives to find his patient, Darlene, sitting on a chair in the medical tent looking diaphoretic and pale. Todd proceeds with his assessment and starts to formulate a treatment plan, which includes calling for a transporting unit.

Note: In this scenario, we will assume that Todd is following the appropriate medical control protocols when assessing and treating this patient.

During Todd’s assessment of the patient, he becomes aware of the fact that he will have to obtain an ECG as part of his treatment plan. He recognizes that he will have to perform a physical exam and to do so, will need informed consent from Darlene to agree to the assessment as well as the ECG, which would include the removal of her sweater and brassiere. Todd also realizes that despite being in the medical treatment area (with no other persons around), it would be appropriate to offer Darlene a blanket to be able to cover herself during part of his assessment if she so chooses.

Todd then focuses his attention on Darlene and goes on to explain to her that he would like to obtain an ECG, why he would like to do so and how the procedure will proceed. After Darlene hears about the steps of the procedure, she gives Todd the informed consent needed to continue with the procedure and all that it will entail.

As soon as Todd receives consent, he then lets Darlene know that he will turn his back for a moment while she removes the necessary clothing and drapes herself with the blanket. Darlene is appreciative of Todd respecting her boundaries in this instance.

Once Darlene finishes undressing, she lets Todd know he can resume with the ECG procedure. Todd explains what actions he will be taking as he begins placing the 12 lead cables and electrodes in the appropriate sequence. He goes on to explain that some breast tissue is covering the optimal placement area where he needs to place the electrodes and offers options on how he can place it, while respecting her boundaries.

Todd lets Darlene know the first option is that Darlene can move her own breast while Todd places the electrodes or, alternatively, the second option would be that he can use the back of his hand to displace the breast tissue. Darlene lets Todd know that she would feel more comfortable moving her own breast. Todd acknowledges and respects Darlene’s boundaries and proceeds to place the electrodes and cables once Darlene moves her own breast tissue.

With Darlene’s cooperation and consent, and in addition to Todd being mindful of her boundaries, he is able to successfully place the electrodes and cables, allowing him to obtain the 12 lead ECG.

In this example, Todd demonstrates his knowledge and adherence to the standard 2.5 – Professional Boundaries in which a regulated member must maintain professional boundaries with patients at all times and in any interaction. He also acts in the patient’s best interest and manages the boundaries within the patient-provider relationship. Finally, he respects that each patient’s boundaries may be unique to their experiences including culture, age, values and experiences with trauma.

As you may know, the Standards of Practice set out the minimum standards in paramedic services. Each regulated member is required to understand and comply with these Standards, but how does this translate in the day-to-day work of EMRs, PCPs, and ACPS?

In an effort to help regulated members understand and apply the Standards to real life situations, we will be sharing scenarios that give context to the Standards and ideas on how to implement this into practice.

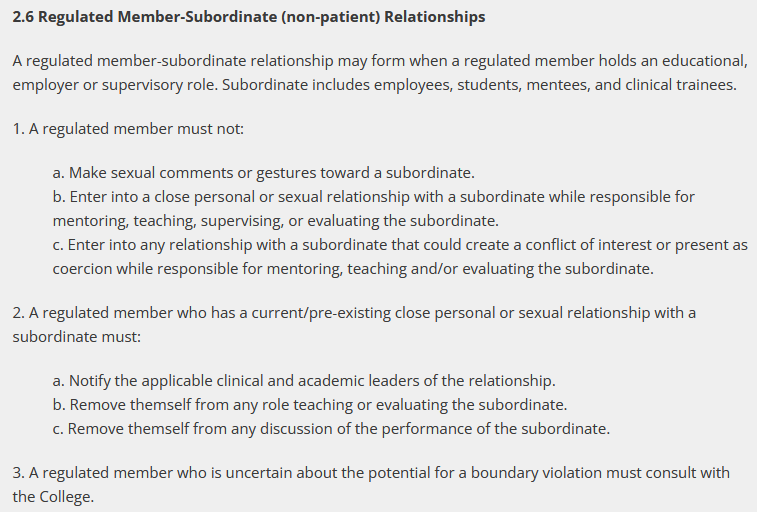

The following scenario will attempt to address defining regulated member-subordinate (non-patient) relationship.

Scenario:

Manpreet is an Advanced Care Paramedic (ACP) who works in the rural community of Red Water. Manpreet and his partner have recently been asked by their supervisor to take on and mentor an ACP student on their final practicum. As Manpreet has successfully mentored many students before, he and his partner agree to take on Malinda as their student. Next tour, Malinda joins Manpreet and his partner on their unit to start her precepting for her final ACP practicum.

The first few tours go well for Malinda, and she is feeling very supported in her learning endeavors on the unit with Manpreet and his partner. Manpreet is an extremely professional, knowledgeable, caring, and charismatic paramedic and it is evident that he is well-liked by patients and colleagues. After spending many hours around Manpreet, Malinda begins to realize she is developing personal and sexual feelings for Manpreet. She decides to discuss her feelings with Manpreet on their next shift.

At the same time, Manpreet is noticing that Malinda’s demeanor changes around him while he is precepting her. She seems more nervous, stumbles over her words, and often seems flushed in the face when he is in close proximity to her on calls. He begins to wonder if there is a potential conflict of interest arising. Manpreet decides he wants to discuss their student/preceptor relationship at the start of next shift and that if she does indeed have an attraction building, that it would be appropriate to potentially remove himself from the role of teaching and evaluating Malinda, his subordinate.

Note: Neither Manpreet or his partner is in a current/pre-existing close personal or sexual relationship with Malinda (subordinate).

Before Malinda sits down with Manpreet to explain her feelings, she confides in her classmate Kate about her feelings towards her preceptor. Kate understands how she could develop these feelings but reminds Malinda that because Manpreet is a regulated member of the Alberta College of Paramedics, he is not allowed to enter into a personal or sexual relationship with a subordinate while he is responsible for mentoring, teaching, supervising or evaluating her. She urges Malinda to contact the College if she is concerned about the potential boundary violation, which Malinda agrees to.

Next shift Malinda and Manpreet sit down to discuss where Malinda is at in her precepting journey. Malinda discloses to Manpreet that she has developed emotional and sexual feelings for him, and it has caused a disruption in her preceptorship. Manpreet listens to Malinda’s concerns and goes on to reference Standard 2.6 – and advises Malinda that it is no longer appropriate to precept her. Together, they agree to notify the clinical and academic leaders of her school to have her placed with another ACP to finish her practicum. No boundaries were violated by Malinda or Manpreet.

In this example, both Manpreet and Malinda demonstrate their knowledge and adherence to the Standard 2.6 – Regulated Member-Subordinate (non-patient) Relationships in which a regulated member-subordinate relationship may form when a regulated member holds an educational, employer or supervisory role. Subordinate includes employees, students, mentees and clinical trainees. In this case, Manpreet did not make sexual comments or gestures toward a subordinate (Malinda). Nor did he enter into a close personal or sexual relationship with a subordinate while responsible for mentoring, teaching, supervising or evaluating the subordinate. Lastly, he did not enter into any relationship with a subordinate that could create a conflict of interest or present as coercion while responsible for mentoring, teaching and/or evaluating the subordinate.

When Manpreet and Malinda sat down to discuss their ongoing regulated member- subordinate relationship, Manpreet decided it would be appropriate to notify the applicable clinical and academic leaders of the relationship shift, remove himself from any role teaching or evaluating the subordinate, as well as remove himself from any discussion of the performance of the subordinate.

As you may already know, the Standards of Practice set out the minimum standards in the provision of paramedic services. Each regulated member is required to understand and comply with these Standards, but how does this translate in the day-to-day work of EMRs, PCPs, and ACPS?

In an effort to help regulated members understand and apply the Standards to real life situations, we will be sharing scenarios that give context to the Standards and ideas on how to implement this into practice.

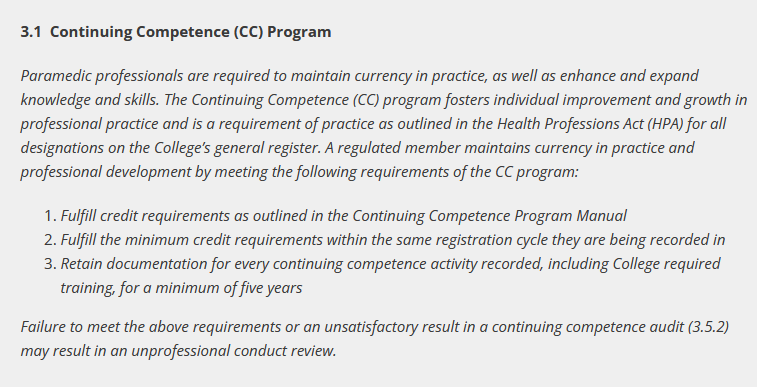

The following scenario will attempt to address the Continuing Competence (CC) program:

Scenario:

Cassandra and Wesley are partners on an ambulance in Vegreville. On one of their shifts, they were discussing the upcoming renewal. Wesley said in passing that he had not completed any CC training all year and didn’t think he would have time before completing renewal. He said to Cassandra that he thought he might enter training he hasn’t completed in order to finish renewal and do the training later. Cassandra knows that it is a professional responsibility to complete CC training every year and providing false information to the College is considered unprofessional conduct. She shows Wesley the Continuing Competence Standard of Practice and lets him know about the College audit process.

Cassandra has done all that she can in this scenario; she informed Wesley of his professional responsibilities and duties and let him know about the possible repercussions for falsifying information to the College. It is each members’ responsibility to complete training and meet all the outlined requirements in their member portal, failure to do so may result in an unprofessional conduct review. In the event Cassandra found out that Wesley did falsify his CC record, she would have a Duty to Report him per section 1.3 of the Standards of Practice.

As you may know, the Standards of Practice set out the minimum standards in paramedic services. Each regulated member is required to understand and comply with these Standards, but how does this translate in the day-to-day work of EMRs, PCPs, and ACPS?

In an effort to help regulated members understand and apply the Standards to real life situations, we will be sharing scenarios that give context to the Standards and ideas on how to implement this into practice.

The following scenario will attempt to address defining restrictions.

Scenario:

Kevin is an Advanced Care Paramedic who has recently returned from parental leave where he was away from the workplace for nine months and not practicing in the field. Kevin is on a gradual return to work where he is riding as a third paramedic on the ambulance for three tours so that he has the ability to regain some confidence in his skills and to ensure that he is comfortable on his own. Kevin is paired with another ACP by the name of Josh, as well as a PCP named Cherie to help with his return.

It is Kevin’s second day of his return to work when he, Josh and Cherie are called for an emergent transfer out of their local community hospital. When Kevin and the crew arrive on scene, the physician and nurses are actively caring for a 50-year-old male patient that had received a life-threatening gunshot wound to the abdomen. As Kevin, Josh and Cherie arrive, the hospital staff ask Kevin to initiate an additional IV line and administer a bag of packed red blood cells while Josh and Cherie start to package the patient for transfer to a surgical facility.

As Kevin is initiating the IV line, he is finding it difficult to concentrate as his thoughts are being consumed by how to administer blood and blood products. He begins racking his brain and trying to remember his training from many years prior and begins to worry that he is not feeling confident in his competence and skill to be able to administer blood safely.

Kevin decides to call Josh over to let him know that he is not feeling comfortable performing this restricted activity (even though he is authorized to perform it) as he doesn’t feel competent to perform the skill in that moment. Kevin also recognizes that this administration of blood is appropriate to the clinical circumstance of this patient.

Recognizing the strength and professionalism that Kevin just demonstrated, Josh reassures Kevin that he will take over the administration of blood for this patient. Josh also lets Kevin know that they can review this skill after the call so that he can feel comfortable next time there is an opportunity to administer blood or blood products. Kevin breathes a sigh of relief and begins to help Cherie prepare and package this patient for transport.

In this example, Kevin and Josh both demonstrate their knowledge and adherence to the Standard 4.0.2 Restriction, where despite any authorization to perform restricted activities, regulated members must restrict themselves to performing only the restricted activities that they are competent to perform. Additionally, members must only perform activities that are appropriate to the clinical circumstance.

Kevin did a good job recognizing that, while he had authorization to perform the administration of blood, he had not done it in several months and didn’t feel comfortable in his level of competency in doing so. By letting his partner Josh know that he didn’t feel competent, Josh was able to step in and administer the blood to the patient in need. Josh did a good job of offering to help Kevin review the administration of blood and blood products after the call so that for the next patient encounter, Kevin could feel confident and competent.

As you may know, the Standards of Practice set out the minimum standards in paramedic services. Each regulated member is required to understand and comply with these Standards, but how does this translate in the day-to-day work of EMRs, PCPs and ACPs?

In an effort to help regulated members understand and apply the Standards to real life situations, we will be sharing scenarios that give context to the Standards and ideas on how to implement this into practice.

The following scenario will attempt to address transfer of care.

Scenario:

Cole and Kristy, both ACPs, are working together on an ambulance in the community of Westlock, located just outside Edmonton. Early in their shift, they are called to a 68-year-old female, Mrs. Linda Parker, who has fallen outside her residence and sustained an open tibia fracture. Upon arrival, they find Mrs. Parker sitting on the ground, visibly distressed, with an open wound on her right leg and the bone protruding. She is alert but in significant pain.

Cole quickly assesses the patient and instructs Kristy to manually stabilize the fracture and apply a sterile dressing to the wound while he obtains vital signs and prepares to manage the pain. Cole follows his employer’s medical control protocols and proceeds to administer a loading dose of 5 mg of morphine IV for pain relief (patient weight is 60 kg). They proceed to stabilize Mrs. Parker’s leg for transport and apply the appropriate dressings while continuously monitoring her vitals and condition.

As they prepare to transfer Mrs. Parker to the hospital, Cole ensures that the following steps are carried out in compliance with 4.2 Transfer of Care standard.

1.Written Summary (i.e. electronic patient care record) provided to receiving healthcare providers which includes the following information:

a) Roles and Responsibilities of the regulated member:

- Paramedic crew: Cole (ACP) led the call, assessed the patient and administered morphine, while Kristy (ACP) assisted with wound care and stabilized the fracture.

b) Pertinent Clinical Information:

- 68-year-old female with an open tibia fracture and exposed bone.

- Vital signs: BP 130/80 mmHg, HR 100 bpm, SpO2 98%, Respirations 22 per min

- 5 mg morphine IV administered with stable post-administration vitals.

c) ECG or other test results:

- Sinus tachycardia

- Blood glucose level (BGL) 4.1 mmol

d) Treatment Plans and Recommendations for Follow-Up Care:

- Immediate X-rays for fracture assessment, possible surgery, and ongoing monitoring for infection or complications.

2.Communication with the Patient:

Before transport, Cole explains to Mrs. Parker the care she has received and the next steps in her care plan: “We’ve stabilized your leg and given you medication to help with the pain. You’ll be transferred to the hospital like you requested, where doctors will take X-rays and decide if surgery is needed.” Cole also speaks with Mrs. Parker’s daughter (with permission) on the phone to let her know the care plan: “Your mother has an open fracture. We’ve stabilized her leg and given her pain relief. She’ll need X-rays and possibly surgery, but she’s stable for now. If you’d like, you can meet us at Westlock Hospital as we should be there in about 15 minutes.”

3.Communication with the Receiving Healthcare Provider:

Upon arrival at the hospital, Cole provides the following verbal report to the ED team: “This is Mrs. Linda Parker, a 68-year-old female with an open tibia fracture, treated with 5 mg morphine IV. Her vitals are stable: BP 130/80 mmHg, HR 100 bpm, SpO2 98%, Respirations 22 per min, BGL 4.1 mmol, ECG – Sinus tachycardia. We’ve applied a sterile dressing and splinted her leg. Recommend X-rays and orthopedic consultation for possible surgery.”

Cole and Kristy assess if they have adequate time to complete their documentation now or if they will need to perform only a verbal report and submit their written report later, in a timely matter. Noting that the submission of a written report is what formally constitutes the transfer of care, Cole and Kristy decide to finish their documentation prior to leaving the hospital. They complete the handover, ensuring all necessary information is communicated clearly to the patient, family, and the receiving healthcare providers/team. The hospital team assumes responsibility for Mrs. Parker’s ongoing care while the paramedics finalize their electronic patient care report.

In this example, Cole and Kristy both demonstrate their knowledge and adherence to the Standard 4.2 Transfer of Care, where a regulated member transferring full or partial responsibility for a patient’s care to another healthcare provider(s) must:

1.Provide to the receiving healthcare provider(s) a timely, written summary that includes the following information:

- Identification of the roles and responsibilities of the regulated member and other healthcare providers involved in patient’s care up to the point of transfer

- Pertinent clinical information

- ECG or other test results

- Treatment plans and recommendations for follow-up care

2. Communicate clearly to the patient the roles and responsibilities of the regulated member and other healthcare providers involved in the patient’s next steps for care.

3. Ensure any referral or alternate care plan or release of care by a paramedic to another regulated healthcare professional is communicated to the patient, family and receiving healthcare provider.